As we usher in the new year, we traditionally look forward and decide how to be better people. As a game designer, I want us all to make better games. Accordingly, I want to address an unfortunate intellectual current I have seen coursing through the indie community as of late. It generally appears under the moniker of “gameplay vs. narrative,” advanced in articles asserting the fundamental incompatibility of narrative and gameplay and suggesting (usually with little to no analysis) that we should discard one (always narrative) in favor of the other (inevitably, gameplay).

This is a close cousin to the visual-centric approach advocated by the Superbrothers, in that it encourages game developers to avoid the use of perfectly legitimate modes of expression in making their games. Both approaches seem to represent little more than the prejudices and predilections of their authors, which would be of little concern but for the zealousness with which they are pushed upon impressionable young developers. I will explain why this narrow approach to game development is bad in a moment. But first, some background.

I am a late adopter by long practice. I become enamored of bands five years after they reach the zenith of their popularity. I buy game consoles one generation behind. And so it is with me listening to this Jonathan Blow lecture about manipulative game design techniques, given at Rice University back in late September of 2010. Granted, I’m late, but hopefully not too late to weigh in.

Slightly more than one hour into the lecture, Blow states that game narrative, attractive visuals, and other game elements beyond core gameplay are manipulative. I won’t put words into his mouth; here is what he says:

The problem that I have is that these good game design things that I talked about–the best practices, at the beginning of this talk–are all, to one degree or another, in either subtle ways or obvious ways, manipulative tactics. And that’s why abstract games like Chess or Go don’t have them, because there’s like nobody there–there’s not enough content in those games to actively manipulate you. But video game designers actively manipulate players all the time.

Now, I have no issue with Blow’s criticism of Skinnerian conditioning in games (which, in fairness to him, comprises the vast majority of his talk). But he clearly thinks that including narrative and beautiful visuals in a game is manipulative as well. To my mind, this position is indefensible.

My first instinct is to argue that some players want to play games primarily for their great characters, thrilling stories, and stunning visuals, and that this is a legitimate reason for a player to play a game. Blow is prepared for this argument, however. He preempts it repeatedly throughout his lecture. We want things that are bad for us all the time, he says. It’s not a matter of volition, or desire, or even of fun–it’s a matter of designing games to not harm people.

This counterargument makes sense when applied, for example, to casino games. Casino games exist solely to bilk their customers of money. A slot machine sports eye-pleasing visuals designed to draw the attention of unwary victims, a bit like a real-life mimic. And that is all there is, as far as visuals or narrative. It’s pure manipulation in order to cause harm.

The “don’t harm players” counterargument also makes sense when applied to games like Farmville or Frontierville. The cutesy, attractive visuals of these games makes them appear non-threatening and accessible, when in reality they are so utterly devoid of meaningful content and so overwhelmingly, deliberately tailored to produce negative feelings in their players that one can actually say that these games are, objectively-speaking, harmful.

But that is as far this counterargument goes. There is nothing inherently disrespectful about presenting visual beauty. There is nothing inherently disrespectful about presenting a good narrative. We do not say that a masterful painting disrespects an art lover, or that a well-paced and entertaining novel disrespects its reader. In most fields of artistic endeavor, to hook a player with interesting visuals or a thrilling story is simply to be a competent artist. Why should these modes of expression suddenly become sinister when used in games?

I believe Blow’s intended point is more that video games are meant to have interesting gameplay, and that using a good story, careful pacing, and attractive visuals to drag the player through a fundamentally uninteresting play experience is abusive.

This is a more defensible point, but still not one I can agree with. It is true that Diablo, World of Warcraft, and other run-around-clicking-to-get-random-reward-drop games are largely designed to get players to continue playing compulsively. Is that is abusive? I think many will agree that the answer is yes. But the moral opprobrium heaped upon these games stems from their abusive game mechanics, not from their graphics or storylines.

We can say the same of RPGs that require players to spend hours grinding through repetitive, tactically barren encounters in order to improve their stats enough to proceed. The abuse lies in the design, not in peppering such a game with beautiful vistas or compelling characters.

In short: Blow distinguishes between manipulating human psychology in order to deliver something beneficial and manipulating human psychology in order to deliver something harmful, but many of those things he calls manipulative are things that are beneficial in themselves! Visual beauty is beneficial.Memorable characters in a well-told story are beneficial.This is, after all, why we treat paintings and novels as art, and not as socially malignant time sinks.

There is a reason why no one makes this sort of argument in other artistic fields. “Oh, that Nabokov: I just know he’s writing that beautiful, beautiful prose to manipulate me into reading his novel.” No serious person would make that sort of argument because the prose is part of the novel. Writing good prose is inherently part of writing a good novel.

Likewise, visuals are (quite obviously) a part of video games. And so is narrative. Not every game, of course, and even when it is there, the narrative is sometimes highly abstracted. But it’s still something that most games possess: even Chess, which Blow credits as a pure game freed from the trappings of story and character. Chess pieces have names and styles of movement that impart character. The very setup of the game tells a story: two kings face off across a battlefield, their queens and loyal advisers by their sides, with rows of sad little pawns lined up at the fore, ready to be marched off to oblivion at the hands of higher-class, better-equipped units. It’s highly abstract, but chess nonetheless suggests a narrative about war and social class. There is even a rags-to-riches narrative embedded in the rules: a pawn who reaches the end of the board gains the chance to overcome the class of its birth, becoming a queen.

This line of argument is a bit disingenuous, though. What narrative and visual elements Chess has are weak, even when elaborated by players through the process of play. Chess endures on the strength of its gameplay alone. There is certainly nothing wrong with this. But there’s nothing particularly right about it, either.

This is the point: although visuals and narrative do not need to be used universally in games, they remain crucial tools for instilling games with meaning.

It’s surprising to hear Blow champion Chess and Go given his purported concern that games should speak to the human condition. Clearly, neither Chess nor Go does much in this regard. I imagine that Blow likes these games because they represent a certain conceptual purity in game design. Games, he might say, are fundamentally about rules and interaction. Everything else is secondary. If we can somehow get games to intelligently comment on the human condition mostly (or, if possible, entirely) via rules and interactions, then we will have realized much of the potential of the medium.

If that is his position, he certainly isn’t alone. Justin Marks, for instance, has adopted a similar position, remarking: “I say stop writing high-minded stories. Start writing games. And let the stories grow from them.”

But why? Interactivity may be what makes games unique, but does that mean that interactivity should be the sole mode that game designers use to impart meaning in a game? It is one thing to say that narrative needs to be well-integrated to mesh with non-linear gameplay, and another thing entirely to say that narrative should be eliminated whenever possible and that game mechanics should be used to deliver a game’s message in its stead.

Granted, game mechanics have the potential to carry a lot of water when it comes to meaning. Game mechanics are about player interaction with a system (or oftentimes, multiple systems). In designing a game’s systems, game developers are able to implicitly comment on the real-world analogs that those systems represent, and let the player absorb that commentary through inductive learning.

Yet, there’s that word: represent. I would humbly suggest that visuals and narrative are key to this process. People do not generally recognize real-world systems within a game because of the particular formulas that govern those systems; to the contrary, they recognize those systems because of symbolism, established both visually and verbally, which invites the player to draw parallels.

Consider Rod Humble’s The Marriage, a game which purports to represent the system of–no surprises–a marriage. There is no narrative, and only the barest of visual symbolism. This was intentional; as Humble put it, “I wanted to use game rules to explain something invisible but real.”

Less intentional was the fact that the game failed to convey its message intelligibly, despite bearing a title which trumpets the game’s intended subject matter to the player. Here’s Rod Humble again: “This is a game that requires explanation. That statement is already an admission of failure.”

Other, more successful “art games” in this vein provide real-world context via visuals and narrative. Every Day the Same Dream, for instance, has the player work through a deliberately linear, looping system that conveys a sense of dreariness and loss of agency. But only through visuals and characters do we know that this dreary system is meant to represent someone’s life revolving around a corporate job. Game mechanics, visuals, narrative: each works in concert to impart a message to the player, and it does so with reasonable success.

Good visuals and a narrative are not just important in some bare-bones, let-the-player-know-what-system-you’re-representing sense, however. They are independently important tools to use in communicating meaning to the player.

Suppose we have a game in which the author wants the player to experience the intractability of poverty. The designers of that game would do well to establish an economic system in the game where the player is confronted with intense scarcity, forcing her to make constant trade-offs between necessities and accrue mounting debt. This can all be represented with numbers displayed on the screen, text labeling each figure for what it represents, and little more: something close to pure game mechanics, in other words.

Should we stop there, then? We could, but it would be a pitiable mistake. Doing so would mean the player never gains a visceral feel for what this system and its numbers mean. We will end up with no tangible sense of the very real consequences of living on a limited income, of rising rents forcing us to move into a neighborhood with no grocery store, of the myriad different ways money pressures lead to a breakdown in our character’s personal relationships. A canny application of stark visuals and non-linear narrative can impart meaning in a far more visceral and effective way to the player than mechanics alone.

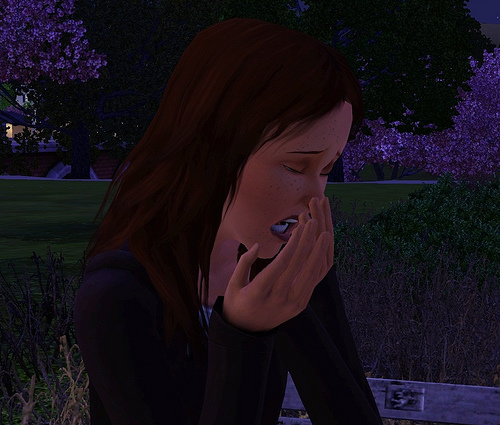

Just look at The Sims 3. The story of Alice and Kev isn’t sad because of the game mechanics that made it possible, although those certainly deserve credit for giving rise to the experience. No; what makes it tragic is the characters, human beings with human foibles unable to overcome adversity in situation after situation. What makes it heartbreaking is seeing how profoundly unhappy they are. It’s visuals; it’s narrative; it’s game mechanics. All three contribute to impart meaning to the player much better than any one or two could standing alone.

From the standpoint of imparting meaning, this is good design. Rather than a puritanical insistence on using only one tool in the game designer’s toolbox, we get an intelligent application of each tool as it is needed in order to craft a compelling experience that successfully delivers a message about our lives and the world we live in.

To be clear: I am not issuing a clarion call for us to start jamming our games full of unnecessary cut scenes, or to force linear stories onto open-ended games. Good integration is important. This is true across all media. Words in music must be used as lyrics, not as a novel. Music in films must be used as score, not as an album. Likewise, narrative and visual elements in games should be implemented to take account of (and credibly support) non-linear gameplay. But they should be used.

Some people will undoubtedly complain that with narrative, this simply is not possible. To those people, I would suggest that maybe they should stop thinking of game narrative as something plot-driven (which, at best, limits the entire game’s structure to something branching) and start thinking of it as something character-driven. Read the story of Alice and Kev. Look at what Doublebear is trying to do with Dead State. Character interactions can be part of a game’s system and drive plot all at once, and do so in a thoroughly non-linear way.

At the end of the day, it is our job as game developers to make this work. It is our role to craft games that effectively communicate our vision. It’s isn’t abuse. It isn’t disrespect. It’s just practicing our craft. That is what artists do, if only we have the skill and clarity of vision to do it right.